Saturday, 27 August 2016

Wednesday, 24 August 2016

Hepatitis

The most common cause of it is virus

-these virus tend to target the cells of the liver

They get in & infect these cells

-they cause them to present abnormal proteins

-CD8 T-cells recognize these abnormal proteins

-then the hepatocyte go through cytotoxic killing of these cell & apoptosis

-it mostly take a place in portal tract & lobules

-As the inflammation progress it produce symptoms:

-fever, malaise, nausea.

-hepatomegaly ( enlarged liver ) & pain.

-increase blood transaminase ( when cell are damage they release the enzymes ALT & AST )

-atypical lymphocytosis

-jaundice ( both conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin)

-dark urine

(These symptoms according to the severity)

If symptoms or virus continue more than 6 months

This gone from being acute to chronic.

At this point it mostly occur in the portal tract & fibrosis occur causing cirrhosis.

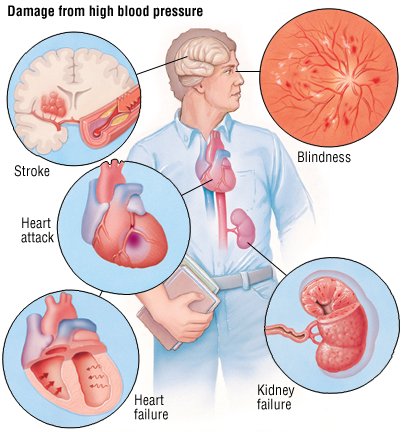

Hypertensive urgency vs. emergency

Urgency

-There is no end organ damage

especially in brain, heart or kidney

-systolic BP > 180

-diastolic BP > 120

How to deal with it ?

-reduce BP from hrs to days

-Quite reduction

Emergency

-end organ damage

ex. Encephalopathy

-CHF

-Retinal hemorrhage we see papilledema by the fundoscope

-stabbing back pain in patient with dissection

How to deal with it?

25% reduction in BP in min/hrs

IV NTG, nitroprusside

( it cause VD to the veins > decreasing the pre and after load > decrease the resistance in the arteries > decrease the BP)

Friday, 19 August 2016

Finger clubbing

Finger clubbing is a thickening of the fingertips that gives them an abnormal rounded appearance.

.

.

What causes finger clubbing?

-

The exact cause of finger clubbing is not known (idiopathic ), but it is a common symptom of respiratory disease, congenital heart disease, and gastrointestinal disorders.

.

.

⭕Respiratory disease causes of finger clubbing:

🔸Bronchiectasis (destruction and widening of the large airways)

🔸Cystic fibrosis (thick mucus in the lungs and respiratory tract)

🔸Lung abscess

🔸Lung cancer

🔸Pulmonary fibrosis (scarring of the lungs)

__

☡Notes:

It is worth noting that clubbing is not associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Indeed, the presence of clubbing in a patient with COPD should prompt a search for an underlying (lung) cancer. .

.

⭕Congenital cardiac disease causes of finger clubbing:

🔸Tetralogy of Fallot (combination of four structural defects).

🔸Transposition of the great vessels (rare condition in which the major vessels entering or leaving the heart are misconnected)

.

. ⭕Gastrointestinal disease causes of finger clubbing:

🔸Celiac disease (severe sensitivity to gluten from wheat and other grains that causes intestinal damage)

🔸Cirrhosis of the liver

🔸Inflammatory bowel disease (includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis)

🔸Liver cancer

.

.

⭕Finger clubbing can also have other causes including:

🔸Acromegaly (gigantism caused by a pituitary tumor).

🔸Atrial myxoma (tumor arising within heart)

🔸Dysentery (infectious inflammation of the colon, causing severe diarrhea).

🔸Endocarditis (inflammation of heart tissue, often infectious).

🔸Graves’ disease (type of hyperthyroidism resulting in excessive thyroid hormone production).

🔸Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cancer of the lymph tissues).

..

14k

Monday, 15 August 2016

Swan neck deformity!

Swan neck deformity

__

is a deformed position of the finger, in which the joint closest to the fingertip is permanently bent toward the palm while the nearest joint to the palm is bent away from it (DIP flexion with PIP hyperextension). It is commonly caused by injury or inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or sometimes familial (congenital, like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).

.

.

.

💡Remember:

..

🏥A 54 -year-old woman presents with swollen,painful hand and feets,Which are "stiffer in the mornings".

On examination there are signs of ulnar deviations and sublaxations of metacarpophalyngeal (MCP) joints .

.

.

✔Dx :Rheumatoid arthritis.

Ulnar devations and sublaxation of joints are signs of advanced disease.

.. ( Rheumatoid Arthritis):

..

-insidious onset.

-hands(PIP, MCP)exceptDIP, Wrist, ankels, knees

-inflammation present.

-systemic findings present.

-hand (Ulnar deviation , Swan nek and Boutnnnir deformity).

-⬆ESR &RF and anaemia

-X-ray (LESS):

L – loss of joint space

E – erosions

S – soft tissue swelling

S – soft bones (osteopenia)

.

Saturday, 13 August 2016

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis causes bones to become weak and brittle — so brittle that a fall or even mild stresses such as bending over or coughing can cause a fracture. Osteoporosis-related fractures most commonly occur in the hip, wrist or spine.

Bone is living tissue that is constantly being broken down and replaced. Osteoporosis occurs when the creation of new bone doesn't keep up with the removal of old bone.

Osteoporosis affects men and women of all races. But white and Asian women — especially older women who are past menopause — are at highest risk. Medications, healthy diet and weight-bearing exercise can help prevent bone loss or strengthen already weak bones.

Symptoms

There typically are no symptoms in the early stages of bone loss. But once your bones have been weakened by osteoporosis, you may have signs and symptoms that include:

* Back pain, caused by a fractured or collapsed vertebra

* Loss of height over time

* A stooped posture

* A bone fracture that occurs much more easily than expected

Causes:

Your bones are in a constant state of renewal — new bone is made and old bone is broken down. When you're young, your body makes new bone faster than it breaks down old bone and your bone mass increases. Most people reach their peak bone mass by their early 20s. As people age, bone mass is lost faster than it's created.

How likely you are to develop osteoporosis depends partly on how much bone mass you attained in your youth. The higher your peak bone mass, the more bone you have "in the bank" and the less likely you are to develop osteoporosis as you age.

Risk factors:

A number of factors can increase the likelihood that you'll develop osteoporosis — including your age, race, lifestyle choices, and medical conditions and treatments.

1-Hormone levels

Osteoporosis is more common in people who have too much or too little of certain hormones in their bodies. Examples include:

* Sex hormones. Lowered sex hormone levels tend to weaken bone. The reduction of estrogen levels in women at menopause is one of the strongest risk factors for developing osteoporosis. Men experience a gradual reduction in testosterone levels as they age. Treatments for prostate cancer that reduce testosterone levels in men and treatments for breast cancer that reduce estrogen levels in women are likely to accelerate bone loss.

* Thyroid problems. Too much thyroid hormone can cause bone loss. This can occur if your thyroid is overactive or if you take too much thyroid hormone medication to treat an underactive thyroid.

* Other glands. Osteoporosis has also been associated with overactive parathyroid and adrenal glands.

2-Dietary factors

Osteoporosis is more likely to occur in people who have:

* Low calcium intake. A lifelong lack of calcium plays a role in the development of osteoporosis. Low calcium intake contributes to diminished bone density, early bone loss and an increased risk of fractures.

* Eating disorders. Severely restricting food intake and being underweight weakens bone in both men and women.

* Gastrointestinal surgery. Surgery to reduce the size of your stomach or to remove part of the intestine limits the amount of surface area available to absorb nutrients, including calcium.

3-Steroids and other medications

Long-term use of oral or injected corticosteroid medications, such as prednisone and cortisone, interferes with the bone-rebuilding process. Osteoporosis has also been associated with medications used to combat or prevent:

* Seizures

* Gastric reflux

* Cancer

* Transplant rejection

4-Medical conditions

The risk of osteoporosis is higher in people who have certain medical problems, including:

* Celiac disease

* Inflammatory bowel disease

* Kidney or liver disease

* Cancer

* Lupus

* Multiple myeloma

* Rheumatoid arthritis

5-Lifestyle choices

Some bad habits can increase your risk of osteoporosis. Examples include:

* Sedentary lifestyle. People who spend a lot of time sitting have a higher risk of osteoporosis than do those who are more active. Any weight-bearing exercise and activities that promote balance and good posture are beneficial for your bones, but walking, running, jumping, dancing and weightlifting seem particularly helpful.

* Excessive alcohol consumption. Regular consumption of more than two alcoholic drinks a day increases your risk of osteoporosis.

* Tobacco use. The exact role tobacco plays in osteoporosis isn't clearly understood, but it has been shown that tobacco use contributes to weak bones.

Thursday, 11 August 2016

Medicine is long term coarse..

Studying medicine is very much a marathon, not a sprint. It is a 5 or 6 year course, where in your final few years holidays become a lot shorter and you are studying almost all year round (instead of having three months off a year). The reason the course is so long is because of the volume of material that needs to be learned; both the basic scientific principles and the clinical skills needed to apply them must be taught. While this may seem like a fairly monumental task the truth is that while at university time seems to pass incredibly rapidly, probably because the average student is so busy they don’t have time to notice each term flying past. While this is nice as it feels as if you’re making rapid progress through your studies it also means it’s very easy to get behind on work and not catch up until the holidays come around. Fortunately the holidays come around so quickly due to the short length of the terms you can usually get away with this and the holidays are often a valuable opportunity to make sure you understand the past term’s work before the chaos of term time starts again. Some academic staff even go as far as to say…

Tuesday, 9 August 2016

Failure !!

GOOD ARTICLE TO READ

Failure

Keiran K. Tuck, MBBS

Neurology August 9, 2016 vol. 87 no. 6 639-640

failed only one exam in medical school. In my second year of medical school, I was given the name and bed number of a patient and told to report back about her medical condition. As the elevator bore me up to the fifth floor of a dark hospital built before the advent of the x-ray machine, I reviewed the blanks of the medical census I needed to fill in: _____ is a ____ year old _____ with a medical history of ____ who presents with ____. At the same time, my stomach stirred with fear of the 3 forbidding senior clinicians who in 30 minutes would be the arbiters of my ability to interact with a real patient.

I walked into a 4-bed hospital room and called out through the curtains to the corner where my patient was supposed to be. A soft groan cued me to enter. Pulling back the curtain, I briefly thought the gray, gaunt figure wrapped in green sheets was a corpse until I noticed her eyes slowly inspecting me. I dutifully introduced myself and sat down to commence my patient history protocol. Her monosyllabic responses were perfect for data collection and my stomach slowed. However, my cataloging of data hit a glitch when I asked the simple closed-ended screening question, “Do you have depression?”

There was no response, so I jumped ahead. “How long have you had depression? Do you take any medications? Have you ever attempted suicide?” Again, silence.

I looked up from my notes to see if she had heard me. Tears ran down her face and my stomach churned in a new direction. Her suffering dissolved my checklist; I didn't know what to do. Timidly, I asked her if she was OK. After what seemed like an eon of silence, she began talking. At first, she spoke slowly then became more animated as her story unfolded. She talked about her fears, her regrets, and her family. I nodded quietly and asked a few follow-up questions. I smiled when she talked about things that made her happy and frowned when she spoke of things that pained her. I learned that she had been born on a sheep farm. She thought she was dying, although no one had told her that. She felt that her smoking had led her to this place and away from her children and that guilt ate at her.

I wish I had been more human and ended our conversation with a hand on her shoulder or even a handshake. Instead, I said something about the time and got up to leave. Fortunately, this amazing lady had one last thing to say. I will always remember the way the dark circles under her eyes made her look almost desperate as she looked up at me and said, “Thank you, you're the best doctor I've met since I've been here.”

I floated down to the first floor, certain that I must have aced the test after such an endorsement. I didn't worry that my note pad was empty after the line “depression?” and that I wasn't exactly sure what I was going to say. My stomach was calm as I sat down in front of the 3 preceptors. Soon, however, the subtle nods of approval that greeted the introduction to my patient's story became cocked eyebrows and sideways glances as I delved into her depression and life story. A sudden “What about her lung disease?” arrested my narrative.

“Oh yes, she has bronchitis—”

“Is it chronic?”

“She's had it for a long time.”

“Does she meet the criteria for chronic bronchitis?”

“I, I don't know.”

“Do you know the criteria for chronic bronchitis?”

“Yes.”

“Did you ask about them?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“I didn't have time. We talked about her depression.”

I think they tried to help me by quizzing me on every possible detail about her lung disease, perhaps hoping they could give me some kind of credit. The clearer it became that I couldn't answer their questions, the more frustrated they became. With stony faces, they pulled their chairs back from the table and quietly conferred among themselves about whether the patient was depressed and what to do with me. They decided to go talk to the patient themselves and left my stomach and me alone. Many minutes later they silently returned to the table. One of them smiled coolly and said, “We talked to the patient, and you're right, she is depressed. However, you failed to address her most serious and concerning medical issue, which was her chronic bronchitis. Thank you, you'll find out your grade next week.” I left the room with my head hung low.

Luckily, the few of us who failed were given a second chance, which I passed by exhaustively cataloging the bowel movements and surgeries of an inflamed colon. However, I felt wronged. How could it be that having such a profound connection with a patient was a failure?

When applying to medical school, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I had no friends or family in medicine. I just knew I was bored in my laboratory job and I wanted to make the world a better place. I wanted to help people. I was thrilled to start the journey. Yet throughout medical school, I became increasingly cynical and distrustful of medicine. In my third year of school, I told my parents that they should avoid doctors at all costs because they were no better than the cold, shallow scientists I had worked with in my previous job at a biotech company.

Scattered throughout the initial years of my medical career I found the occasional oasis of humanity. A young girl with mononeuritis multiplex due to cryoglobulinemia thanked me for taking the time to talk to her and her boyfriend about the effects of cyclophosphamide on her fertility. A middle-aged woman who was aphasic after a large intracerebral hemorrhage pulled me over and spoke her first words … “I love you.” A Greek family struggling with what to do with their hemiplegic and aphasic patriarch thanked me for mediating. These events all felt special to me, but seemed to be ignored by the physicians around me. Here were people who needed help. Here were opportunities to make the world a better place, but few seemed interested. “Consult social work,” “That's PT's problem,” and “There's nothing we can do,” were common refrains. Discussions about whether a stroke was due to obstruction of the recurrent artery of Huebner or a lenticulostriate artery were interesting but to me were less important than how the patient was going to eat without the use of an arm. I felt out of place in medicine. I felt angry. I felt I'd made a mistake. Without great enthusiasm, I started a neurology residency with the goals of doing my work, getting paid, and going home.

Thankfully, my residency program decided that I should spend some time with physicians who felt it was their job to put humanity on par with science. I spent a month with our inpatient palliative care team and my perspective on the doctor–patient relationship changed profoundly. I learned there was more to death than cessation of heart and brain function and that death is often about those left behind. But more important, I learned about suffering. I learned that tremor is not always the problem. The problem may be the patient's inability to tie flies and cast a rod. I learned that a spouse's lack of time to live his or her own life may be more important than the burden of amyloid in a patient's brain. I learned that a DNR decision is not an acute problem, rather one that should be discussed years in advance of being implemented. Most important, I learned that I am not alone in feeling that the cold science of medicine needs to be tempered by the warmth of humanity.

Today, I have a much better opinion of medicine. I don't see my fellow physicians as cold, lab coat–wearing scientists. I see them as good people who have been taught to fill in blanks rather than listen, but who are changing themselves because their passion is to improve patient care. I have encouraged my parents to complete an advanced directive and find physicians they are comfortable talking to. Furthermore, I am heartened that the principles of palliative care are being recognized in the medical literature, especially in the field of neurology.1,2 Finally, I realize that the patient who triggered this journey was more than depressed. She was suffering. However, she did not suffer from lack of a cure. She was suffering because her physicians thought there was nothing they could do. Because of her, I realize that I can always help my patients even if I do not have a cure or treatment for the breakdown of their body.

I am glad I failed.

Saturday, 6 August 2016

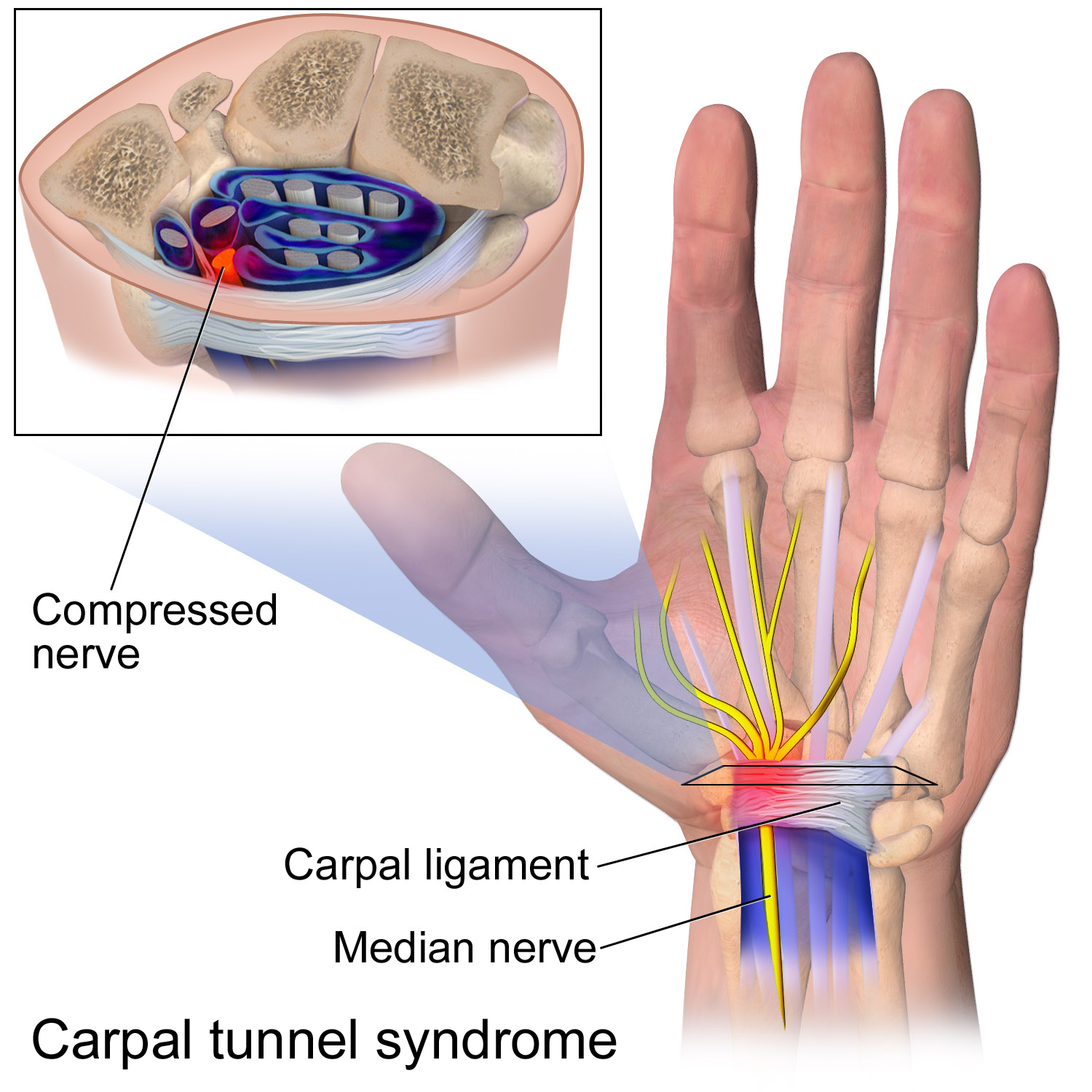

Carpal tunnel syndrome

carpal tunnel syndrome is a narrow passageway located on the palm side of your wrist. This tunnel protects a main nerve to your hand and the nine tendons that bend your fingers.

Compression of the nerve produces the numbness, tingling and, eventually, hand weakness that characterize carpal tunnel syndrome.

Fortunately, for most people who develop carpal tunnel syndrome, proper treatment usually can relieve the tingling and numbness and restore wrist and hand function.

Heartburn

Despite its name, heartburn has nothing to do with the heart . Some of the symptoms, however, are similar to those of a heart attack or heart disease.

Heartburn is an irritation of the esophagus that is caused by stomach acid. This can create a burning discomfort in the upper abdomen or below the breast bone.

With gravity's help, a muscular valve called the lower esophageal sphincter, or LES, keeps stomach acid in the stomach. The LES is located where the esophagus meets the stomach -- below the rib cage and slightly left of center. Normally it opens to allow food into the stomach or to permit belching, then closes again. But if the LES opens too often or does not close tight enough, stomach acid can reflux, or seep, into the esophagus and cause the burning sensation.

Occasional heartburn isn't dangerous, but chronic heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can sometimes lead to serious problems.

Heartburn is a weekly occurrence for up to 20% of Americans and is very common in pregnant women .

What causes heartburn?

The basic cause of heartburn is a lower esophageal sphincter, or LES, that doesn't tighten as it should. Two excesses often contribute to this problem: too much food in the stomach (overeating) or too much pressure on the stomach (frequently from obesity, pregnancy, or constipation). Certain foods commonly relax the LES, including tomatoes, citrus fruits, garlic, onions, chocolate, coffee, alcohol, caffeinated products, and peppermint. Meals high in fats and oils (animal or vegetable) often lead to heartburn, as do certain medications. Stress and lack of sleep can increase acid production and can cause heartburn. And smoking , which relaxes the LES and stimulates stomach acid, is a major contributor.

Source: webmed

Source: webmed

Thursday, 4 August 2016

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common disorder that affects the large intestine (colon). Irritable bowel syndrome commonly causes cramping, abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhea and constipation. IBS is a chronic condition that you will need to manage long term.

Even though signs and symptoms are uncomfortable, IBS — unlike ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, which are forms of inflammatory bowel disease — doesn't cause changes in bowel tissue or increase your risk of colorectal cancer.

Only a small number of people with irritable bowel syndrome have severe signs and symptoms. Some people can control their symptoms by managing diet, lifestyle and stress. Others will need medication and counseling.

The signs and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome can vary widely from person to person and often resemble those of other diseases. Among the most common are:

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- A bloated feeling

- Gas

- Diarrhea or constipation — sometimes alternating bouts of constipation and diarrhea

- Mucus in the stool

For most people, IBS is a chronic condition, although there will likely be times when the signs and symptoms are worse and times when they improve or even disappear completely.

When to see a doctor

Although as many as 1 in 5 American adults has signs and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome, fewer than 1 in 5 who have symptoms seek medical help. Yet it's important to see your doctor if you have a persistent change in bowel habits or if you have any other signs or symptoms of IBS because these may indicate a more serious condition, such as colon cancer.

Symptoms that may indicate a more serious condition include:

- Rectal bleeding

- Abdominal pain that progresses or occurs at night

- Weight loss

Causes

t's not known exactly what causes irritable bowel syndrome, but a variety of factors play a role. The walls of the intestines are lined with layers of muscle that contract and relax in a coordinated rhythm as they move food from your stomach through your intestinal tract to your rectum. If you have irritable bowel syndrome, the contractions may be stronger and last longer than normal, causing gas, bloating and diarrhea. Or the opposite may occur, with weak intestinal contractions slowing food passage and leading to hard, dry stools.

Abnormalities in your gastrointestinal nervous system also may play a role, causing you to experience greater than normal discomfort when your abdomen stretches from gas or stool. Poorly coordinated signals between the brain and the intestines can make your body overreact to the changes that normally occur in the digestive process. This overreaction can cause pain, diarrhea or constipation.

Triggers vary from person to person

Stimuli that don't bother other people can trigger symptoms in people with IBS — but not all people with the condition react to the same stimuli. Common triggers include:

- Foods. The role of food allergy or intolerance in irritable bowel syndrome is not yet clearly understood, but many people have more severe symptoms when they eat certain things. A wide range of foods has been implicated — chocolate, spices, fats, fruits, beans, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, milk, carbonated beverages and alcohol to name a few.

- Stress. Most people with IBS find that their signs and symptoms are worse or more frequent during periods of increased stress, such as finals week or the first weeks on a new job. But while stress may aggravate symptoms, it doesn't cause them.

- Hormones. Because women are twice as likely to have IBS, researchers believe that hormonal changes play a role in this condition. Many women find that signs and symptoms are worse during or around their menstrual periods.

- Other illnesses. Sometimes another illness, such as an acute episode of infectious diarrhea (gastroenteritis) or too many bacteria in the intestines (bacterial overgrowth), can trigger IBS.

Lifestyle and home remedies

In many cases, simple changes in your diet and lifestyle can provide relief from irritable bowel syndrome. Although your body may not respond immediately to these changes, your goal is to find long-term, not temporary, solutions:

- Experiment with fiber. When you have irritable bowel syndrome, fiber can be a mixed blessing. Although it helps reduce constipation, it can also make gas and cramping worse. The best approach is to slowly increase the amount of fiber in your diet over a period of weeks. Examples of foods that contain fiber are whole grains, fruits, vegetables and beans. If your signs and symptoms remain the same or worse, tell your doctor. You may also want to talk to a dietitian.Some people do better limiting dietary fiber and instead take a fiber supplement that causes less gas and bloating. If you take a fiber supplement, such as Metamucil or Citrucel, be sure to introduce it slowly and drink plenty of water every day to reduce gas, bloating and constipation. If you find that taking fiber helps your IBS, use it on a regular basis for best results.

- Avoid problem foods. If certain foods make your signs and symptoms worse, don't eat them. These may include alcohol, chocolate, caffeinated beverages such as coffee and sodas, medications that contain caffeine, dairy products, and sugar-free sweeteners such as sorbitol or mannitol.If gas is a problem for you, foods that might make symptoms worse include beans, cabbage, cauliflower and broccoli. Fatty foods also may be a problem for some people. Chewing gum or drinking through a straw can lead to swallowing air, causing more gas.

- Eat at regular times. Don't skip meals, and try to eat about the same time each day to help regulate bowel function. If you have diarrhea, you may find that eating small, frequent meals makes you feel better. But if you're constipated, eating larger amounts of high-fiber foods may help move food through your intestines.

- Take care with dairy products. If you're lactose intolerant, try substituting yogurt for milk. Or use an enzyme product to help break down lactose. Consuming small amounts of milk products or combining them with other foods also may help. In some cases, though, you may need to stop eating dairy foods completely. If so, be sure to get enough protein, calcium and B vitamins from other sources.

- Drink plenty of liquids. Try to drink plenty of fluids every day. Water is best. Alcohol and beverages that contain caffeine stimulate your intestines and can make diarrhea worse, and carbonated drinks can produce gas.

- Exercise regularly. Exercise helps relieve depression and stress, stimulates normal contractions of your intestines, and can help you feel better about yourself. If you've been inactive, start slowly and gradually increase the amount of time you exercise. If you have other medical problems, check with your doctor before starting an exercise program.

- Use anti-diarrheal medications and laxatives with caution.If you try over-the-counter anti-diarrheal medications, such as Imodium or Kaopectate, use the lowest dose that helps. Imodium may be helpful if taken 20 to 30 minutes before eating, especially if you know that the food planned for your meal is likely to cause diarrhea.In the long run, these medications can cause problems if you don't use them correctly. The same is true of laxatives. If you have any questions about them, check with your doctor or pharmacist.

source: http://www.mayoclinic.org/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)